Investment Philosophy

Systematic Wealth Management seeks to address a persistent yet straightforward problem. Despite decades of evidence showing that active managers consistently underperform their benchmarks, many investors still rely on expensive, traditional active strategies. In study after study, from early work by Jensen to modern SPIVA scorecards, the majority of active managers underperform, and the few that succeed do so inconsistently, making them nearly impossible to identify in advance. At the same time, a century of market history and academic research has reshaped how we understand investing, demonstrating that markets efficiently incorporate information into prices, diversification reduces risk, and that disciplined exposure to well-understood risk factors drives long-term returns.

Our answer is an evidence-based, rules-driven approach to investing that builds on traditional indexing to target factors of higher expected returns. Instead of chasing stories, timing markets, or betting on star managers, portfolios are constructed to harness factors identified in the academic literature, such as market, size, and value. These factors are implemented through transparent, index-like strategies. This systematic, factor-oriented approach seeks higher expected returns than a plain market‑cap index while preserving the core strengths of passive investing: broad diversification, low turnover, and a transparent, repeatable process. The result is an investment philosophy grounded in how markets actually work, designed to give thoughtful investors a more reliable path to long-term success than the mainstream Wall Street playbook.

Introduction

Investing is an inherently difficult pursuit. Financial markets form a complex, buzzing web of high-frequency data that often overwhelms even the most disciplined observers. At times, markets can seem almost unknowable. Trying to make sense of it all can feel like navigating through a blizzard, fixating on each snowflake as it flutters by, losing sight of the larger storm.

Investors today face an ever-expanding array of choices for navigating this complexity. From retail traders to institutional professionals, everyone seems to have their own view of what works best. Many of these convictions are shaped as much by portrayals of the stock market in popular culture and the financial media as by rigorous empirical evidence. When investors share their next “big idea,” it almost always revolves around two elements: speculation about future prices and a story to justify them.

In the mid-20th century, a convergence of science, technology, and data sparked a revolution in finance. For the first time, academic researchers began applying the scientific method to financial markets, testing hypotheses, uncovering insights, and deepening our understanding of how markets actually work. Economic theory coupled with empirical evidence began to shed light on what had once seemed unknowable, challenging long-held beliefs and the very orthodoxies of Wall Street.

At Systematic Wealth Management, we help investors look beyond the constant storm of news, opinions, and speculation. Instead of being swept up in the swirl of market narratives, we anchor our philosophy in academic research and empirical evidence. We offer clarity and resilience when the market’s noise is at its loudest. We seek to turn investing from a guessing game into a process guided by reason, insight, and enduring principles. Before we go further, let’s define a few basic things about the market.

What Is “The Market”?

When we refer to the market, we mean the secondary markets for securities. In most people’s minds, this is the secondary market for equity shares in publicly traded companies. When transactions occur in the secondary market, shares that are already in existence are exchanged between two participants. One party sells shares to another party, who buys them at an agreed upon price. These transactions occur on exchanges around the world, averaging $ 836.3 billion in daily trading volume [1], as market participants assess information and decide on a transaction price. We view the market as an information-processing machine whose job is to incorporate new information into security prices.

Can You Really Beat the Market?

This question has plagued investors for decades. When people talk about “beating the market,” they usually refer to their performance relative to a benchmark. Many investors think of the S&P 500 as “the market,” but it is actually just a large-cap index composed of the 500 largest publicly traded companies in the United States. There are many other publicly traded companies in the United States and around the world, so if we are to evaluate performance, we need a like-for-like comparison with an appropriate benchmark. If someone primarily invests in small caps or international markets and says they outperformed the S&P 500, it isn’t really a valuable way to assess their performance.

One of the most well-known studies assessing the performance of active management is the S&P Index Versus Active (SPIVA) series. SPIVA compares the performance of actively managed mutual funds against their appropriate benchmarks. The results paint a pretty bleak picture for active management. In a given year, about half of active managers will underperform. But as you evaluate their performance over extended time periods, more managers underperform, with the overwhelming majority of active managers underperforming on a 20-year horizon [2].

| 1-Year (%) | 5-Year (%) | 10-Year (%) | 15-Year (%) | 20-Year (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| US Large Cap | 65.24 | 76.26 | 84.34 | 89.50 | 91.99 |

| US Small Cap | 29.69 | 60.37 | 82.22 | 90.68 | 90.80 |

| Europe | 85.23 | 91.89 | 93.10 | — | — |

| Japan | 62.00 | 84.93 | 85.85 | 81.46 | — |

| United Kingdom | 72.01 | 82.20 | 82.02 | — | — |

| Canada | 88.73 | 92.54 | 95.51 | — | — |

| Australia | 55.63 | 73.84 | 82.71 | 85.13 | — |

Source: S&P Global Market Intelligence, SPIVA Scorecard

As for managers who outperform over long periods, the data shows they tend to do so inconsistently. Active managers who are top performers one year often fall into lower-performing groups the next. This inconsistency raises the question of whether their ability to outperform the market is due to luck or skill. If their ability to beat the market is a skill, shouldn’t they consistently outperform the market year after year? Or are their returns better explained by random chance?

Why Active Management Persists

Despite mounting evidence to the contrary, the Wall Street orthodoxy of active management prevails. We believe this persistence stems from three core drivers: compelling narratives are more emotionally satisfying than statistics; the financial industry’s compensation structure rewards assets under management regardless of outcome; and the profoundly human desire to believe we can beat the odds. To understand how we got to this point, it’s helpful to examine the historical evolution of financial markets and investment practices.

Historical Evolution

Investing and trading of securities dates back to the 1600s, beginning with the Dutch East India Company’s shares trading on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange. Since then, financial markets have enabled investors to fund and participate in the growth of some of the most innovative companies in history. To understand the current state of financial markets and investment in the United States, we’ll examine three distinct eras, beginning with the decades leading up to the Great Depression, which we refer to as the speculative era.

Pre-Great Depression: The Speculative Era

As investors, we can best understand the speculative era as the time in market history before the widespread adoption of fundamental analysis. It was an era marked by market manipulation, speculative manias, and dramatic crashes. Few companies released detailed or reliable financial statements, and standardized accounting practices were virtually nonexistent. Conducting fundamental analysis on an individual company was exceedingly difficult, as investors had to rely on information from corporate insiders or the financial press, which was often inaccurate or incomplete.

Instead, investment decisions were shaped by the reputations of companies, promoters, and bankers, with word of mouth and personal relationships playing a significant role. Investors tended to favor established companies with regular dividend payments, viewing this as a sign of stability and financial health. Advice from investment bankers and brokers often reflected their own interests or insider connections rather than objective analysis. Speculative impulses, rumors, and tips from social circles or well-connected insiders frequently drove stock selection. Market manipulation was commonplace, as minimal regulatory oversight allowed small groups of investors to exert significant influence over prices.

In the 1920s, financial information began to circulate more widely, prompting a gradual shift toward fundamental analysis. Early approaches focused primarily on balance sheet analysis because it was the most accessible financial data. Professional investment management expanded during the decade’s stock market boom, with investment trusts gaining popularity rapidly. In 1924, there were 49 investment trusts; by March 1927, this number had surged to 179. By 1929, the growth was explosive, with over one billion dollars flowing into investment trusts in just the first eight months. Yet these early investment vehicles were often highly leveraged and speculative. Many were financed through brokers’ loans and complex capital structures, leaving them vulnerable to market downturns. When the stock market crash of 1929 struck, the ensuing depression decimated these funds, starkly revealing the dangers of excessive leverage and inadequate regulation.

Great Depression and WWII: Regulation and Fundamental Analysis

The Great Depression through the end of World War II marked a transformative era for the U.S. stock market. Out of the 1929 crash and subsequent economic depression emerged a framework of federal regulation that laid the foundation for modern financial markets. The period also witnessed the rise of fundamental analysis and a growing skepticism toward Wall Street’s unchecked claims.

Regulation

The Securities Act of 1933 became the cornerstone of federal securities regulation[3]. Often referred to as the “truth in securities” law, it established mandatory disclosure requirements and prohibited fraud, deceit, and misrepresentation in the sale of securities. Under the Act, companies seeking to issue securities had to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and file detailed registration statements and prospectuses that outlined the company’s business operations, management, financial statements, and associated risks.

Soon after, the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 created the SEC and granted it broad oversight authority[4]. The Act empowered the SEC to regulate securities exchanges and broker-dealers, enforce anti-fraud and market manipulation provisions, and oversee proxy solicitation rules involving shareholder communications. By centralizing regulatory authority at the federal level and promoting a disclosure-based regulatory philosophy, these acts fundamentally reshaped U.S. market oversight and investor protection.

Benjamin Graham and the Birth of Value Investing

Benjamin Graham emerged as a pioneering figure in the development of fundamental analysis. The 1934 publication of Security Analysis, co-authored with David Dodd, marked the formal birth of modern fundamental analysis and value investing[5]. By advocating for a systematic evaluation of corporate financial statements, Graham and Dodd established the intellectual groundwork that continues to influence professional investment practice and academic finance.

A central tenet of Graham’s philosophy is that investing should be guided by rational analysis and anchored in a security’s intrinsic value rather than its market price. Intrinsic value refers to a company’s perceived worth as determined by analyzing fundamentals such as earnings, balance sheets, and cash flows. Value investors seek opportunities where the market price is significantly below this intrinsic value, expecting that price and value will eventually converge.

Graham used rational analysis to distinguish between investment and speculation. He argued that investment required a long-term perspective and focus on risk management, rather than the pursuit of short-term speculative gains. To manage risk, Graham introduced the concept of the margin of safety. He theorized that securities priced well below their intrinsic value provide a built-in margin of safety against analytical errors, unforeseen market events, and the inherent uncertainties of investing. Such securities, he maintained, should be given priority.

Early Skepticism Toward Wall Street

The publication of Security Analysis marked a turning point for investment management. For the first time, investors had a systematic framework to analyze the standardized financial reporting mandated by the Securities Acts of 1933 and 1934. A company’s actual financial condition was now disclosed in detailed securities filings and quarterly reports. Armed with these new tools and data, fundamental analysis moved from the margins to the mainstream.

The promise was compelling: through rigorous analysis of financial statements, skilled financial analysts could identify securities trading below their intrinsic value, delivering superior returns to their clients. Wall Street embraced this vision enthusiastically. Yet embedded in this belief is the assumption that the market misprices securities and that a diligent analyst can uncover insights that thousands of other market participants have not yet recognized. For this to be true, an analyst must possess either superior information or superior analytical ability—seeing what others cannot see, or understanding what others fail to understand. As more analysts applied the same techniques to the same publicly available information, this assumption became increasingly difficult to sustain.

Even as Wall Street promoted its analytical prowess, skepticism began to mount. In 1940, Fred Schwed published Where Are the Customers’ Yachts?, a satirical yet devastating critique of the investment industry[6]. The title itself told the story, while bankers and brokers could afford yachts from their fees and commissions, their customers rarely achieved similar success, despite dutifully following professional advice. Schwed exposed a fundamental conflict of interest. Wall Street thrived regardless of client results, profiting from activity and advice rather than from actual investment performance. This skepticism would set the stage for a revolution in finance, one that would challenge not only the practices of Wall Street, but the very foundations of how we understand markets and investment.

The Big Bang of Academic Finance

The postwar era in the United States marked a convergence of technological advancement, expanding market data, and emerging academic research. Often referred to as the “Big Bang,” this period sparked a revolutionary transformation in how we understand markets, risk, and investing. Before this era, most theories about financial markets and investing relied heavily on anecdotal evidence. In contrast, the postwar decades saw the rise of modern financial theory, driven by pioneering mathematical models and empirical research. These advances replaced speculative, narrative-driven investment approaches with rigorous quantitative frameworks.

To illustrate these developments, we’ll take a closer look at four influential papers from the “Big Bang” era that redefined our understanding of markets and investing.

Harry Markowitz – Portfolio Selection (1952)

The revolution began with Harry Markowitz’s doctoral dissertation in 1952, titled “Portfolio Selection,” which introduced Modern Portfolio Theory[7]. Before Markowitz’s work, investors focused on selecting individual securities without considering how they interacted within a portfolio. Modern Portfolio Theory posited that investors should evaluate securities not in isolation, but also consider how they contribute to the overall risk-return profile of the entire portfolio.

William Sharpe – Capital Asset Prices: A Theory of Market Equilibrium under Conditions of Risk (1964)

Building on Markowitz’s work, Sharpe’s 1964 paper introduced the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM)[8]. CAPM established that risk and return are related by proposing that there are two types of risk:

1. Systematic – Market Risk

2. Unsystematic – Company Specific Risk

CAPM formalized the understanding that diversification can eliminate company-specific risk. For instance, a portfolio of 30-50 stocks can eliminate most company specific risk, but market risk remains and cannot be eliminated through diversification. Therefore, it should be compensated by higher expected returns.

Michael Jensen – The Performance of Mutual Funds in the Period 1945-1964 (1968)

Published in The Journal of Finance in May 1968, Jensen’s study was the first comprehensive empirical test of professional money management performance[9]. The study analyzed 115 mutual funds using Jenson’s Alpha, a risk-adjusted performance measure based on the CAPM. The study found that, on average, mutual funds did not outperform the market. It demonstrated that only a few individual funds showed statistically significant outperformance beyond what would be expected by chance. The study was instrumental in the development of index funds and brought the question of whether outperformance could be attributed to luck or skill into the debate.

Eugene Fama – Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work (1970)

Eugene Fama published a series of papers in the 1960s exploring the concept of market informational efficiency, or how quickly markets incorporate new information into prices[10]. To this day, the efficient market hypothesis is one of the more polarizing theories in finance. The efficient market hypothesis states that “A market in which prices always ‘fully reflect’ available information is called ‘efficient.” In its simplicity lies its complexity, implying that markets immediately incorporate new information into stock prices. Therefore, if markets are efficient, then stock price movements are unpredictable, and efforts to identify undervalued or overvalued stocks through fundamental analysis will not work any better than random chance.

Indexing Revolution

Research from the big bang era fundamentally altered the trajectory of investment management and opened the door for someone to devise a better way. The index fund represents one of the most transformative financial innovations and serves as a powerful intellectual counterweight to Wall Street. Although Jack Bogle and Vanguard are widely recognized as the leading advocates of passive investing, the concept originated in 1960 with Edward Renshaw and Paul Feldstein’s paper, “The Case for an Unmanaged Investment Company,” published in the Financial Analysts Journal[11]. In the paper, the authors identified three main issues with active management:

1. Overwhelming choice

2. Underperformance

3. High Costs

They proposed a radical solution: create an “unmanaged investment company” that would track the market average rather than try to beat it. Their argument was straightforward: while investors would “forego the possibility of doing better than average,” they would “never do significantly worse” while enjoying lower costs. The index fund was conceptualized as a form of downside protection against underperformance. Offering a guarantee of market returns.

Wall Street reacted with intense skepticism, dismissing the concept. Jack Bogle, then a portfolio manager at Wellington Management and a staunch advocate of active management, wrote a rebuttal to the paper in the Journal of Finance. In his rebuttal, he argued that the concept was unrealistic because the technology didn’t exist to efficiently operate a fund[12]. Yet by 1964, a team at Wells Fargo set out to tackle the technical challenges, ultimately launching the first institutional index fund in 1971[13].

Before becoming a champion of index funds, Jack Bogle was a fund manager at Wellington Management during the “Go-Go Years” of the 1960s. The era was a period of rapid growth and extraordinary enthusiasm, as a surge of new investors flooded Wall Street and drove trading volumes to record highs. Professional money management boomed with aggressive, growth-oriented mutual funds led by star managers chasing returns in the Nifty Fifty. The speculative frenzy ended with a severe bear market of 1969-70, highlighting the risks of excessive optimism. Following a failed merger with another asset manager, Bogle was dismissed from Wellington Management. Through clever maneuvering, he remained involved by leveraging Wellington’s corporate structure to launch Vanguard[13]. Seeing an opportunity to experiment with a new kind of investment model, Bogle established a fund complex that operated “at cost,” leading to the creation of the first publicly available index mutual fund.

The Vanguard 500 Index Fund began as a disappointment, with its 1976 launch attracting only about $11 million of the $150 million fundraising goal[13]. Derided as “Bogle’s Folley,” indexing remained a tiny share of U.S. Equity assets through the 1980s. Early adopters were mainly a handful of institutions, and cost-conscious retail investors were persuaded by evidence that most active managers failed to beat the market after fees. Over time, the combination of Bogle’s low-cost mutual fund structure and, in the 1990s, the introduction of ETFs like SPDR S&P 500 gradually broadened the reach of passive investing.

Beginning in the 2000s, indexing moved from niche to mainstream as expanding performance studies highlighted the persistent underperformance of active funds. Asset managers engaged in intense “fee wars,” driving expense ratios on flagship index funds and ETFs toward single-digit basis points. At the same time, regulatory and fiduciary pressures pushed advisors and retirement plans toward cheaper, benchmark-tracking vehicles. These forces produced a sustained flow pattern from active equity funds into passively managed index mutual funds and ETFs, especially after the Global Financial Crisis.

Systematic Investing Framework

Index funds put findings from the big-bang era of academic research into practice, splitting investment management into two divergent worldviews. While elements of research and modern portfolio theory eventually found their way into active management, the investment philosophy was, at its core, focused on identifying securities perceived to be mispriced.

As index funds were on their multi-decade rise, academic researchers continued their inquiries into financial markets. New data and increased computing power paved the way for an evolution beyond the passive investing approach of market-capitalization-weighted index funds. Systematic investing emerged as the next-generation investment strategy, grounded in academic research yet focused on higher returns.

Systematic investing uses quantitative methods to test and identify attributes of securities that lead to higher expected returns. These attributes or “factors” are then targeted using index-like investments. But instead of using market-cap weighting, indexes are constructed around “factors” expected to generate higher returns. This deviation from market-cap weighting is often referred to as a “factor” tilt.

At Systematic Wealth Management, our systematic investing style is based on fundamental factors. Think of it as a modern interpretation of the value investing principles outlined by Graham and Dodd, backed up by academic research and empirical evidence. Eugene Fama and Ken French provide a good overview of fundamental factors in their 1993 paper, “Common Risk Factors in the Returns of Stocks and Bonds”[14]. The paper identifies three factors for stock returns and two factors for bonds, described below:

Stock Factor: Market

Stocks outperform bonds. The market factor is the premium investors demand to bear the systematic risk in stocks that cannot be diversified away. It represents the excess return of the market portfolio over the risk-free rate, or, in other words, the additional return you would expect as an investor buying stocks rather than U.S. Treasuries.

Stock Factor: Size

Small companies outperform large companies. The size factor is the higher return in small companies compared to large companies. Small companies are riskier than large firms; therefore, they have higher expected returns.

Stock Factor: Relative Value

Value outperforms growth. Instead of focusing on intrinsic value, an absolute, subjective measure, systematic investors use relative value, where the price of a security is evaluated relative to other securities in the market. Value and growth are defined by objective metrics: high book-to-market ratios (high book value relative to market price) indicate value stocks, while low book-to-market ratios indicate growth stocks. Fama and French showed that over the long term, value stocks outperform growth stocks.

Bond Factor: Term

Bonds with longer maturities offer greater returns. The maturity of debt instruments plays an essential role in the risk-return relationship. Bonds with longer maturities command a higher expected return, but that higher return comes with greater risk. For investors, increasing duration is worthwhile up to a point, beyond which longer-duration securities offer risk-adjusted returns worse than those of shorter-duration securities.

Bond Factor: Credit

Bonds with higher credit risk offer higher returns. The credit rating of the fixed-income securities plays an important role in their risk-return relationship. Within investment-grade bonds, as credit ratings decline, returns increase. However, once the credit rating becomes “junk” or non-investment-grade, the risk increases significantly.

Beyond the Core Factors

Subsequent research has refined and built upon the original three factors identified by Fama and French[14]. While their model provides a strong foundation, later studies have identified additional factors beyond size, value, and market risk. The Fama-French five-factor model added profitability and investment (quality) factors, demonstrating that companies with robust operating profitability and conservative investment profiles tend to deliver higher expected returns[15]. Momentum, the tendency for stocks that have performed well in the recent past to continue outperforming in the short term, has been well documented[16]. However, its implementation can be challenging for long-term, buy-and-hold investors due to higher turnover and trading costs.

This dynamic highlights an important consideration: the factors identified in academic research are often significantly reduced in real-world implementation due to frictions such as trading costs, liquidity constraints, and tax effects. Investors should not assume that historical backtests or published factor premiums will translate directly into realized returns. The proliferation of factor research in recent years, with more than 1,500 reported factors, underscores the need for careful discernment. The mere existence of a statistical relationship in the data does not ensure its practical investability or long-term persistence.

Systematic investing, therefore, involves a series of informed, subjective decisions: which factors to target, how to define and measure them, and how to combine them within a portfolio. Individual factors can experience prolonged periods of underperformance, testing investor discipline as returns lag benchmarks. Investors must be prepared for greater drawdowns, higher tracking error, and the possibility that factor premiums may differ from expectations. Ultimately, systematic investing is about intentionally accepting different sources of risk to pursue higher long-term rewards.

Is Systematic Investing Active or Passive?

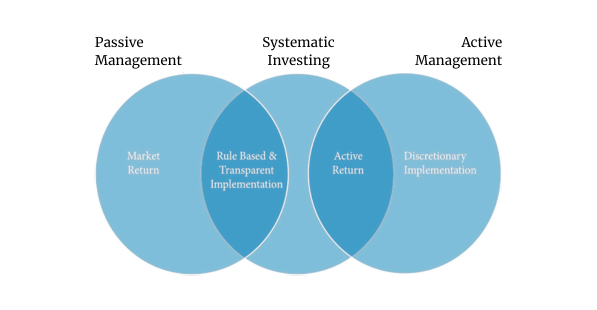

Systematic investing sits somewhere between active and passive management, combining an active return objective with a passive, rules-based implementation[17]. It is best understood by separating what investors are trying to achieve from how they go about doing it.

Active management seeks to outperform a benchmark and deliver active returns. This goal is typically pursued through discretionary decisions such as security selection and market timing, with outcomes heavily dependent on the portfolio manager’s judgments. Passive management, by contrast, aims to match a benchmark’s return, using transparent index-tracking rules and minimizing costs and turnover.

Systematic investing shares the active manager’s goal of outperforming a benchmark, but uses the transparent, rules-based approach of passive strategies. In this sense, it occupies the middle ground between two opposing worldviews.

Philosophically, we are passive investors seeking an active return. The key distinction between active and passive lies in their views of market pricing: active managers assume markets frequently misprice securities and can reliably identify those mispricings, whereas passive investors assume prices are, on average, accurate. Systematic investors accept market prices and then use decades of data and academic research to decide which factors of higher expected return to emphasize. When factors outperform, the outcome is not attributed to exceptional manager talent but to markets working as we expect based on the research. By accepting market prices and applying academic insights in a rules-based, transparent way, systematic investing becomes a disciplined framework for seeking active returns without abandoning the evidence-based foundations of passive investing.

Conclusion

Over the past century, our understanding of how financial markets work has undergone a profound transformation. We have moved from an era defined by speculation, manipulation, and insider connections, where investors made decisions based on rumors and tips, to an era informed by rigorous science, mathematical models, and empirical evidence. This evolution was not linear or inevitable. It required pioneers like Benjamin Graham, academics like Markowitz, Sharpe, Jensen, Fama, and French to challenge conventional wisdom, and visionaries like Jack Bogle to democratize access to better investment approaches. Each generation built upon the insights of the previous one, gradually illuminating what had once seemed unknowable.

Yet despite a century of evidence, many investors and investment managers continue to operate according to the old playbook. They chase performance, time markets, pick stocks based on conviction rather than evidence, and pay for underperformance through high fees and trading costs. The SPIVA data is clear: most active managers underperform their benchmarks over any meaningful time horizon. This underperformance is not due to a lack of intelligence or effort. Instead, it reflects a fundamental truth about markets: it is rare to beat the market through active management over long periods.

This fundamental truth about markets should not discourage investors. In fact, it should liberate them. If you cannot reliably beat the market, why not work with it? The key is to understand how markets work, harness the returns they provide, and manage risk intelligently. Systematic investing shines by combining the rigor of academic research with the discipline of rules-based portfolio management. It offers a path that neither traditional active nor passive management can.

Our commitment is to bring this evidence-based approach from the academic literature into practice, constructing portfolios that align with how markets actually work rather than how Wall Street portrays them. As you consider your investment strategy, we invite you to review how your portfolio measures against these evidence-based principles. We encourage you to ask hard questions: What evidence supports your current approach? Are you paying for performance you could achieve at a lower cost? Are you bearing risks that markets don’t reward? Are you chasing narratives or following empirical evidence?

We believe that thoughtful investors deserve better answers than what Wall Street provides. We believe that the evidence of active management’s underperformance is compelling. And we believe that by grounding our approach in a century of market history and academic research, we can help you build a portfolio positioned for long-term success. That is our commitment to you.

References

[1] Dimensional Fund Advisors. (2025) Pursuing a better investment experience [White paper]. Retrieved from https://my.dimensional.com/pursuing-a-better-investment-experience

[2] S&P Global Market Intelligence. (2024). SPIVA US Scorecard: Year-end 2024. S&P Global.

[3] Securities and Exchange Commission. (1933). Securities Act of 1933. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.sec.gov/rules-regulations/statutes-regulations#secact1933

[4] Securities and Exchange Commission. (1934). Securities Exchange Act of 1934. U.S. Government Publishing Office. https://www.sec.gov/rules-regulations/statutes-regulations#secexact1934

[5] Graham, B., & Dodd, D. L. (1934). Security analysis (1st ed.). McGraw-Hill.

[6] Schwed, F. (1940). Where are the customers' yachts? A good-humored satire of Wall Street. John Wiley & Sons.

[7] Markowitz, H. M. (1952). Portfolio selection. The Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/2975974

[8] Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. The Journal of Finance, 19(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.2307/2977928

[9] Jensen, M. C. (1968). The performance of mutual funds in the period 1945–1964. The Journal of Finance, 23(2), 389–416. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325404

[10] Fama, E. F. (1970). Efficient capital markets: A review of theory and empirical work. The Journal of Finance, 25(2), 383–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/2325486

[11] Renshaw, E. F., & Feldstein, P. J. (1960). The case for an unmanaged investment company. Financial Analysts Journal, 16(2), 43–46. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v16.n1.43

[12] Armstrong, J.B. (1960) The Case for Mutual Fund Management. Financial Analysts Journal 16(3), 33–38. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v16.n3.33

[13] Wigglesworth, R. (2021). Trillions: How a band of Wall Street renegades invented the index fund and changed finance forever. Portfolio/Penguin.

[14] Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns of stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(93)90023-5

[15] Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2015). A five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 116(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2014.10.010

[16] Carhart, M. M. (1997). On persistence in mutual fund performance. The Journal of Finance, 52(1), 57–82. https://doi.org/10.2307/2329556

[17] Bender, J., Briand, R., Melas, D., & Aylur Subramanian, R. (2013). Foundations of factor investing (Research Insight). MSCI Inc. https://www.msci.com/documents/1296102/1336482/Foundations_of_Factor_Investing.pdf